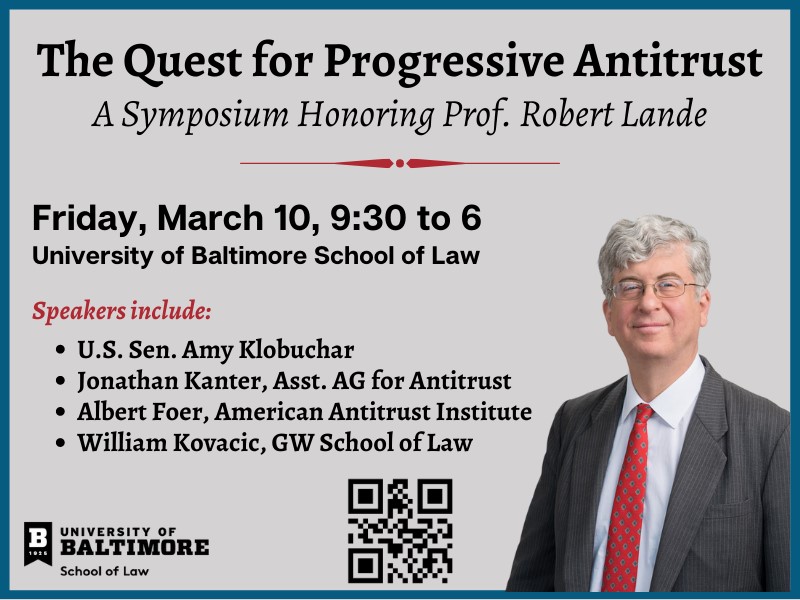

Scan the QR code above or click here for more details.

Kanye West May Not Be Able To “Runaway”[1] from His Latest Controversial Comments: Family of George Floyd Files $250 Million Lawsuit Against West for Disparaging Remarks

*Nicholas Balzano

I. Introduction

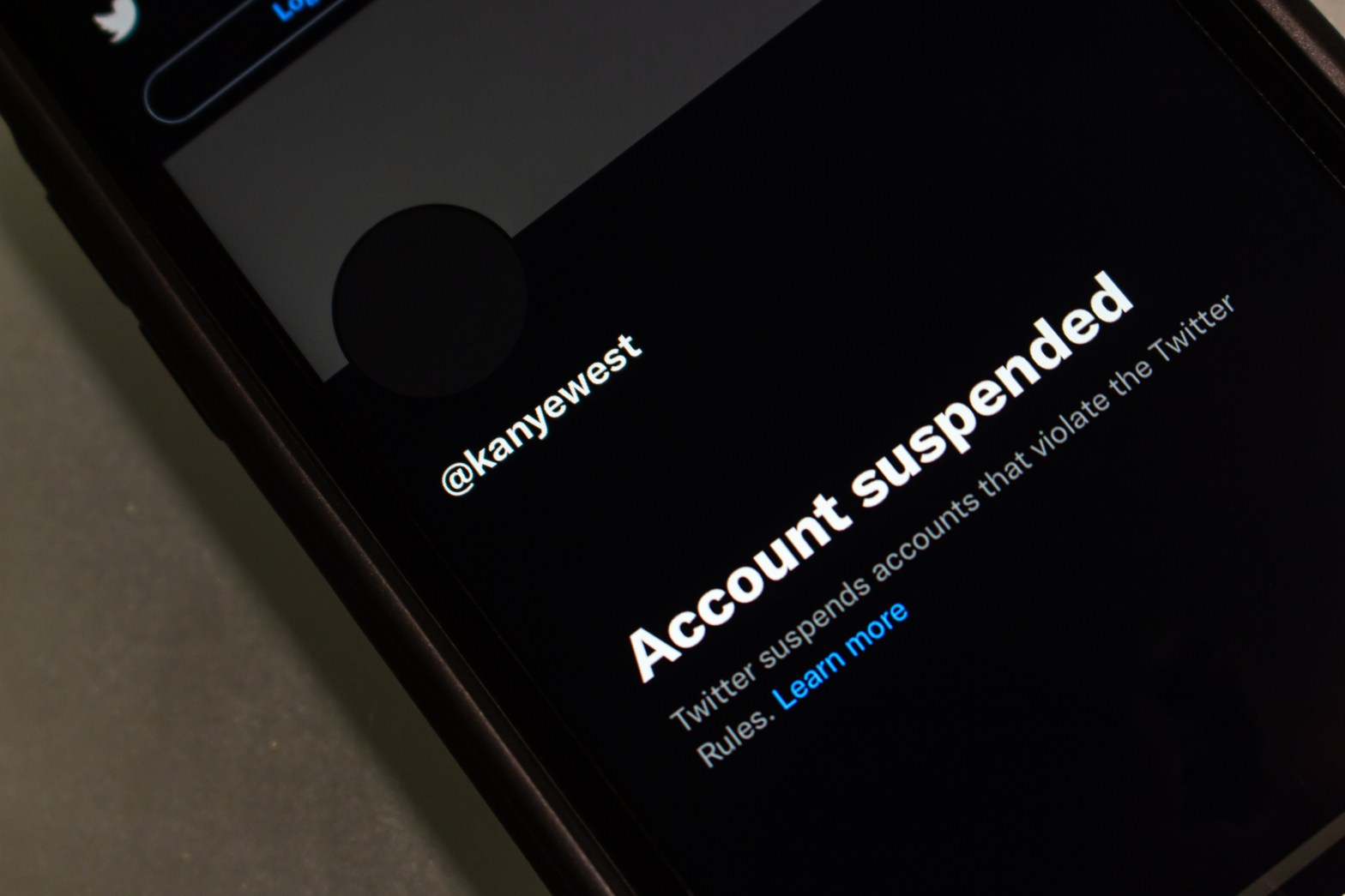

Kanye West (West) is no stranger to drama,[2] but his latest comments may have finally landed him in serious legal trouble.[3] Just weeks removed from posting on his Twitter account that he was going to go “death con 3 on JEWISH PEOPLE,”[4] a comment which resulted in West getting banned from both Facebook and Twitter,[5] West went onto the podcast Drink Champs and claimed that George Floyd (Floyd) died due to a fentanyl overdose.[6] West’s comments about Floyd were blatantly false; the “Hennepin County Medical Examiner’s Office ruled that Floyd’s death was a homicide, caused by Derek Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck for over eight minutes.”[7]

Upon hearing West’s comments about Floyd, the Floyd family announced their intention, through their attorneys at the Witherspoon Law Group, to sue West, his business partners, and his associates “for harassment, misappropriation, defamation, and infliction of emotional distress” for a total sum of $250 million in damages.[8] This suit is highly reminiscent of a recent claim against the famous conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, in which a jury found that Jones must pay “$965 million to the families of eight Sandy Hook shooting victims” after Jones “creat[ed] a fake narrative that the mass shooting was a hoax.”[9] If the outcome in the Jones case is any indication, it would seem that West could face a similar consequence.

II. What Is the Floyd Family Claiming in Their Suit?

In addition to legal claims of “harassment, misappropriation, defamation, and infliction of emotional distress,”[10] the Floyd family also claims that West’s words have hurt Floyd’s daughter, and “creat[ed] an unsafe and unhealthy environment for her.”[11] The Floyd family’s attorneys have stated that “Kanye’s comments are a repugnant attempt to discount George Floyd’s life and to profit from his inhumane death” and that they will “hold Mr. West accountable for his flagrant remarks.”[12] The family has stated that “[f]ree [s]peech [r]ights do not include harassment, lies, misrepresentation, and the misappropriation of George Floyd’s legacy.”[13] While the Floyd family has made several claims in their suit, the allegation of intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED) may provide their most likely route to victory.[14]

III. How Can the Floyd Family Prevail in Their Lawsuit Against West?

According to Roy S. Gutterman, the director of the Tully Center for Free Speech at Syracuse University, the “[Floyd] family may have an uphill battle” against West on the matter of First Amendment rights.[15] Gutterman points out that “there is no possibility of a defamation action” in this case because there is “no living plaintiff whose reputation has been damaged.”[16] However, Gutterman does see a potential path to victory for the Floyd family on their claim of IIED.[17]

On October 12, 2022, a jury in Connecticut handed down a massive victory for some of the families who lost their loved ones in the Sandy Hook massacre.[18] One of the central claims at issue in the case was the claim of intentional infliction of emotional distress as a result of Alex Jones’ statements that the entire massacre was a government hoax.[19] The families of the Sandy Hook victims claimed that the comments made by Alex Jones turned their lives post-Sandy Hook “into years of torment”[20] and that “Jones [had] made it so they [couldn’t] escape” the trauma the mass shooting had inflicted.[21] For example, Mark Barden, who lost his son in the shooting, claimed that due to Jones’ comments, his seven-year-old son’s grave had been “urinated on” and that those who believed Jones’ that the shooting was a hoax had even gone so far as to threaten to dig up his son’s coffin.[22] The families of the Sandy Hook victims prevailed on their claim of IIED, and Alex Jones was made “to pay nearly $1 billion” due to his flagrantly false comments.[23]

Given the outcome of the Sandy Hook case, Floyd’s family may have a good chance at claiming that West’s comments have caused the harm necessary to satisfy the elements of IIED.[24] According to Gutterman, for the Floyd family to succeed on such a claim, they will need to “prove that the statements were intentional or reckless, outside the bounds of accepted decency and morality and causally-connected to some viable harm.”[25]

Analyzing West’s statements under this framework, it appears that the Floyd family may have a good argument to win on their claim of IIED. Under the first prong, West’s statements do not appear to be intentional under the Second Restatement approach which requires an intention to inflict the emotional distress,[26] however, the statements by West are more likely reckless as they were in “deliberate disregard of a high degree of probability that emotional distress” will occur.[27] The second requirement, that the statements be outside the bounds of accepted decency, appears to be satisfied as Floyd’s death was a highly charged issue and by claiming that Floyd’s death was the result of drugs, West undermines the seriousness of Floyd’s death at the hands of the police.[28] West’s statements likely satisfy the element of conduct outside the bounds of decency put forth in the Second Restatement of Torts that, upon hearing the objectionable statements, “an average member of the community would arouse his resentment against the actor.”[29] The last prong also appears to be satisfied as West’s statements are likely causally-connected to the harm suffered by Floyd’s daughter that is alleged by the family.[30] Given this analysis of the IIED requirements, the Floyd family may be successful on their claim against West.

IV. Conclusion

Kanye West is well-known for his erratic behavior, but he may have taken it too far this time. With his recent false claims against George Floyd and concerning behavior, West was dropped by some of his highest-profile sponsors, including Balenciaga, Vogue, and GAP.[31] On top of those brands dropping him, West now faces the $250 million lawsuit from Floyd’s family.[32] With the jury’s decision in Alex Jones’ case, celebrities may learn that now, more than ever, their speech can have serious ramifications. While West has been able to avoid serious legal consequences for his previous antics, this large lawsuit by the Floyd family should have West considering going “Off The Grid” for good this time.[33]

*Nicholas Balzano is a second-year day student at the University of Baltimore School of Law, where he is a Staff Editor for Law Review, a member of the Royal Graham Shannonhouse III Honor Society, and a member of the Honor Board. Prior to law school, Nicholas worked as a law clerk at Atkinson Law. During his 1L summer, Nicholas interned with the Honorable Audrey J.S. Carrión, Administrative Judge and Chief Judge for the Circuit Court for Baltimore City.

[1] Kanye West, Runaway, on My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy (UMG Recordings, Inc. 2010).

[2] See Charlotte Begg, “It Hurts my Feelings”. All the Drama between Kanye West and the Kardashian . . . and Everyone Else., MamaMia (Oct. 5, 2022), https://www.mamamia.com.au/kanye-west-kardashians-drama/.

[3] See Matt Adams, The Family of George Floyd Plans to File a $250 Million Lawsuit Against Ye, NPR, (Oct. 19, 2022), https://www.npr.org/2022/10/19/1129747423/kanye-west-george-floyd-lawsuit.

[4] Loree Seitz, Kanye “Ye” West Apologizes for Anti-Semitic ‘Death Con’ Comments: ‘I Caused Hurt and Confusion’, Yahoo, (Oct. 19, 2022), https://www.yahoo.com/now/kanye-ye-west-apologizes-anti-223700055.html; Sarah McCann, What does Defcon 3 mean? Kanye ‘Ye’ West’s Antisemtic Comment Explained-how did Adidas and Spotify Respond, NationalWorld, (Oct. 27, 2022), https://www.nationalworld.com/news/people/what-does-defcon-3-mean-kanye-ye-wests-antisemitic-comment-explained-how-did-adidas-spotify-respond-3894636 (“Defcon is an abbreviation of the term Defence readiness condition which is used by the US Military. Defcon 3 means ‘force readiness increased above normal levels’ and would mean there is ‘increased regional tensions with possible U.S. force involvement.’”)

[5] Id.

[6] See Daniel Kreps, Kanye West Blames George Floyd’s Death on Fentanyl, Not Police Officer’s Knee, Rolling Stone,(Oct. 16, 2022),https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/kanye-west-george-floyd-drink-champs-1234612069/.

[7] Adams, supra note 3.

[8] The Witherspoon Law Group, Facebook, (Oct. 18, 2022), https://www.facebook.com/witherspoonwewin/posts/pfbid02CYAb5U7BDpNDFfAhEXQUy3SwyvhFkyf217EJRmiJg5qGmzVdZha92uT7eGb8yY4Rl.

[9] Safia Samee Ali, Alex Jones Must Pay $965 Million in Damages to Families of 8 Sandy Hook Victims, NBC News, (Oct. 12, 2022), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/alex-jones-must-pay-965-million-in-damages-to-families-of-8-sandy-hoo-rcna51200.

[10] The Witherspoon Law Group, supra note 8.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] See Adams, supra note 3.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] See id.

[18] See Ali, supra note 9.

[19] See id.

[20] Dave Collins, Alex Jones Ordered to Pay $965 Million for Sandy Hook Lies, AP News, (Oct. 12, 2022), https://apnews.com/article/shootings-school-connecticut-conspiracy-alex-jones-3f579380515fdd6eb59f5bf0e3e1c08f.

[21] Ali, supra note 9.

[22] Collins, supra note 20.

[23] Id.

[24] See Adams, supra note 3; Restatement (Second) of Torts § 46(1) (Am. L. Inst. 1965).

[25] See Adams, supra note 3.

[26] Restatement (Second) of Torts § 46 cmt. (h)(i) (Am. L. Inst. 1965).

[27] Id.

[28] See Adams, supra note 3.

[29] Id. § 41 cmt. (d).

[30] Id.; see The Witherspoon Law Group supra note 8.

[31] See Jordan Hart, Kanye West Refuses to be Canceled Despite Vogue and Balenciaga Being the Latest Among these Fashion Companies to Sever Ties, Business Insider, (Oct. 22, 2022), https://www.businessinsider.com/balenciaga-gap-yeezy-adidas-fashion-brands-dumped-kanye-west-2022-10.

[32] See Adams, supra note 3.

[33] Kanye West, Off The Grid, on Donda (UMG Recordings, Inc. 2021).

Marijuana Expungement in Maryland: Ready for Reform?

*Natalie Murphy

I. Introduction

Maryland recently voted to legalize recreational cannabis after decades of political activism on the issue.[1] However, legalization alone is not enough to fix the damage decades of racist cannabis enforcement imposed on Black Marylanders.[2] An expungement provision in Maryland’s House Bill 837 (HB 837) seeks to recognize the unequal history of marijuana enforcement.[3] The new law legalizes possession of up to 2.5 ounces of marijuana for Marylanders over twenty-one, and automatically expunges all criminal marijuana possession records.[4] How does HB 837 compare with Maryland’s prior expungement reform efforts? Could automatic marijuana possession expungements help ameliorate decades of racist marijuana enforcement as we enter the era of legalization? Maryland’s historically conservative view towards expungement reform indicates that while HB 837 represents a positive development, expungement is a necessary but insufficient tool for social equality and requires significant reformation before it can truly benefit Marylanders with criminal records.[5]

II. What is Expungement?

Expungement eliminates a criminal charge or conviction from an individual’s record.[6] Theoretically, an individual whose record has been expunged is treated as if the incident never occurred.[7] However, not all records can be expunged.[8] Many states bar expungement for violent crimes, civil offenses, or for individuals who have committed subsequent crimes.[9] Expungements are rare at the federal level, and are largely handled by state governments.[10] States vary in their expungement regimes and commonly only allow expungement after a statutory period ranging between three and fifteen years.[11]

Many people with criminal records (by some estimates, twenty-five to thirty percent of U.S. citizens[12]) welcome expungements because criminal records carry a high degree of stigma that raises many barriers.[13] Employment is a significant challenge for individuals with criminal records, and in Maryland, many potential employers seek pre-employment criminal background checks.[14] Beyond employment, housing access is often contingent on submitting a criminal record report, and the Fair Credit Reporting Act takes arrest and conviction history into account when determining credit access.[15] Some states deny benefits like SNAP (Supplemental Nutritional Program) or TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) to those with drug-related convictions.[16] Courts also consider prior criminal history when determining custody and domestic rights.[17] To complicate matters, criminal records often include arrests and non-convictions, which decision-makers without a legal background may regard negatively even though the record does not amount to a conviction.[18] By removing barriers to necessities like employment and housing, expungements serve a personal and social good by increasing opportunities for Marylanders with criminal records.[19]

Despite the social utility of expungements, the process for obtaining an expungement is often complex and lengthy.[20] Maryland recommends, but does not require, utilizing a lawyer for the expungement process.[21] Eligibility for an expungement can take up to fifteen years in Maryland, and any other charges associated with the incident in question must also be expungable.[22] Those seeking to expunge convictions must pay a $30 filing fee.[23] Assuming all forms are filled out correctly, the statutory period is met, the fees are paid, and the expungement is eligible, the approval process takes up to ninety days.[24] The process is also not always fully effective: even when expunged, many states have poor enforcement procedures that allow private agencies, like background check companies, to continue accessing records post-expungement.[25]

III. Maryland’s Expungement Reform History

Maryland historically takes a conservative approach to expungement, and has been slow to implement change despite critical holes in the State’s expungement system.[26] Maryland passed its first piece of legislation limiting public access to criminal records with the 2015 Second Chance Act (Act).[27] The Act allows individuals to “shield” possession charges, including those for marijuana, after three years.[28] Shielding makes records inaccessible to the general public but offers a lower degree of privacy than expungement.[29] Although a historic act, the legislation is riddled with exceptions, the most significant of which authorizes employers to view shielded records with permission.[30] This provision greatly hampers the Act’s intent to increase employment opportunities for Marylanders with criminal records.[31]

Maryland expanded expungement opportunities for individuals with low-level marijuana charges in the October 17, 2017 reform to Maryland Criminal Procedure § 10-105.[32] This change authorized expungement for civil marijuana possession charges of ten grams or less after four years under Maryland Criminal Procedure § 5-601.[33] Beginning October 1, 2021, Maryland implemented a rule authorizing automatic expungement after three years for marijuana possession charges concluding in acquittal, dismissal, not guilty, or nolle prosequi.[34] While both changes represent shifting norms surrounding marijuana possession records, they encompass only small changes, and are far from overhauling the possession expungement system.

Maryland’s expungement law has several additional rules complicating expungements, such as the unit rule and subsequent conviction period. Under the “unit rule,” individuals can only get a record expunged if all other charges from the incident in question are also expungable.[35] Given the number of charges Maryland considers non-expungable, this is a massive barrier for otherwise expungable charges.[36] Subsequent convictions also pose a problem for expungement—an individual convicted of another crime during the statutory waiting period is not eligible for expungement until the statutory period for the subsequent conviction terminates.[37]

IV. Expungement and Social Justice

Many states have made efforts to recognize decades of racist drug enforcement in tandem with legislation legalizing marijuana.[38] Marijuana legalization has instigated a “Green Boom” of high-profit businesses that drive hundreds of millions in state tax dollars, yet returns little to the Black and Latino communities most impacted by the War on Drugs.[39] According to Adam Vine, a marijuana justice organizer in California, pairing legalization efforts with attempts to undo old harms is crucial because otherwise, “[l]egalization is just theft.”[40] Vine suggests expungement can help repair the damage.[41] But before expungement can truly be useful for rehabilitating individuals with marijuana convictions, Maryland needs to clarify and enforce standards for the private storage of expunged records.[42] Additionally, Maryland must discontinue the practice of allowing decision makers to request expunged records—a practice that frustrated the intensions of the 2017 Second Chance Act.[43]

Even under perfected standards, expungement “should be viewed as one piece of a larger puzzle aimed at alleviating the plight of those with criminal records.”[44] Expungement alone could never ameliorate the negative impacts of a decades-long racist drug war.[45] Illinois advocates advocate for more than just expungements—they want reparations.[46] Tyrone Muhammad, a founder of Ex-Cons for Social Change, explains “[e]xpungement alone doesn’t deal with 20, 30, 50 years of incarceration and destruction to our communities by taking [B]lack men off the streets . . . [e]x-cons who were taken away for marijuana need to see our fair share of profit after all we and our families have been through.”[47]

Appropriate as Muhammed’s argument may be, paying financial reparations to Black Americans in recognition of slavery’s legacy and ties to the modern criminal legal system has yet to gain wide-spread public support.[48] Despite the amount of discussion brought by Baltimore native Ta-Nehisi Coates’s The Case for Reparations, there is even less recognition specifically surrounding reparations for racist marijuana enforcement in Maryland.[49] In light of calls for reparations and more radical approaches to recognizing the history of marijuana enforcement, expungement thus represents a necessary but small step in the right direction.

V. Conclusion

Expungement remains one of the few tools available for promoting equality in the face of shifting marijuana norms. Expungements in Maryland are already hampered by privacy exceptions and complex protocols that limit their utility. To truly confer protection to Marylanders with past possession charges, current expungement laws require significant modification. However, given Maryland’s hesitation to alter expungement laws generally, the passage of House Bill 837 marks a massive shift in state expungement protocol for marijuana that could pave the way for increased reforms elsewhere.

*Natalie Murphy is a second-year J.D. candidate at the University of Baltimore Law School. She is currently interning at the Forensics Division of the Maryland Office of the Public Defender and intends to be a public defender in Baltimore City after graduating. She is fascinated by the relationship between science and the law and thinks reading science fiction is crucial for helping everyone (but especially lawyers) imagine a better world.

[1] Nehemiah Bester & Neydin Milián, A War on Marijuana, Or a War on Black Communities?, Am. C.L. Union Md. (Feb. 2, 2022, 5:00PM), https://www.aclu-md.org/en/news/war-marijuana-or-war-black-communities.

[2] See id.

[3] Hannah Gaskill, Lawmakers Weigh the Feasibility of Expungement Post-Cannabis Legislation, Md. Matters (Oct. 28, 2021), https://www.marylandmatters.org/2021/10/28/lawmakers-weigh-the-feasibility-of-record-expungement-post-cannabis-legalization/.

[4] H.D. 837, 2022 Legis. 444th Sess. (Md. 2022).

[5] See infra section IV.

[6] Div. Pub. Ed., What is Expungement?, Am. Bar Assoc. (Nov. 20, 2018), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/publications/teaching-legal-docs/what-is-_expungement-/.

[7] Id.

[8] Brian M. Murray, Retributive Expungement, 169 U. Penn. L. Rev. 665, 689 (2021).

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Brian M. Murray, A New Era for Expungement Law Reform? Recent Developments at the State and Federal Levels, 10 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 369 (2016).

[12] Michelle Natividad Rodriguez & Maurice Emsellem, 65 Million “Need Not Apply”: The Case for Reforming Criminal Background Checks in Employment, Nat’l Emp. L. Proj. 27, ¶ 2 (Mar. 2011), https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/65_Million_Need_Not_Apply.pdf.

[13] Murray, supra note 10, at 365–67.

[14]Criminal Records and Employment, MD. Dept. Disabilities, https://mdtransitions.org/criminal-records-and-employment/ (last visited Jan. 3, 2022).

[15] Murray, supra note 10, at 365.

[16] Darrel Thompson & Ashley Burnside, No More Double Punishments: Lifting the Ban on SNAP and TANF for People with Prior Felony Drug Convictions, Ctr. L. & Soc. Pol’y. (Apr. 2022). https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/no-more-double-punishments/.

[17] Murray, supra note 10, at 365.

[18] Kyla D. Craine & Glenn E. Martin, Returning Citizens: How Shifting Law and Policy in Maryland Will Help Individuals Return from Incarceration, 46 U. Balt. L. Forum 1, 4 (2015).

[19] Rebecca Vallas et al., A Criminal Record Shouldn’t Be a Life Sentence to Poverty, Ctr. Am. Prog. (May 28, 2021), https://www.americanprogress.org/article/criminal-record-shouldnt-life-sentence-poverty-2/s.

[20] Murray, supra note 7, at 668.

[21] Expungement: How to Expunge Court Records,MD Courts, https://mdcourts.gov/sites/default/files/court-forms/ccdccr072br.pdf (last updated Sep. 2022).

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Id.

[25] Murray, supra note 10, at 380–81.

[26] Id. at 372; Matthew R. Braun, Re-Assessing Mass Incarceration in Light of the Decriminalization of Marijuana, 49 U. Balt. L. Forum. 24, 28–9 (2018).

[27] Craine & Martin, supra note 14, at 7; Md. Code. Ann., Crim Proc. § 10-301 (West, 2022).

[28] Md. Code. Ann., Crim Proc. § 10-303 (West, 2022).

[29] Md. Code. Ann., Crim Proc. § 10-301(e) (West, 2022).

[30] Murray, supra note 10, at 370–71; Craine & Martin, supra note 17, at 7.

[31] Craine & Martin, supra note 17, at 7.

[32] Braun, supra note 20, at 29.

[33] Md. Code Ann., Crim. Law § 5-601 (West, 2022).

[34] Md. Code. Ann., Crim. Proc. § 10-105.1 (West, 2022).

[35] Md. Code Ann., Crim. Proc. § 10-107 (West, 2022).

[36] Md. State Bar Assoc., Expungements: What an Attorney Needs to Know (May 15, 2020), https://www.msba.org/expungements-what-an-attorney-needs-to-know/

[37] Md. Code Ann., Crim. Proc. § 10-110 (West, 2022).

[38] See Toni Smith-Thompson & Yusuf Abdul-Qadir, How Legalizing Cannabis Makes the Case for Reparation, Am. C. L. Union N.Y. (Apr. 9, 2021), https://www.nyclu.org/en/news/how-legalizing-cannabis-makes-case-reparations; Jenni Avens, In the Time of Luxury Cannabis, It’s Time to Talk About Drug War Reparations, Quartz Mag. (Jan. 25, 2019), https://qz.com/1482349/weed-and-reparations (describing efforts to correct past wrongs in California’ marijuana enforcement).

[39] Avens, supra note 37.

[40] Id.

[41] Id.

[42] Murray, supra note 10, at 379–380.

[43] See Murray, supra note 10, at 370; Craine & Martin, supra note 17, at 8.

[44] Murray, supra note 10, at 378.

[45] Bester & Milián, supra note 1 (explaining the enduring legacy of racism in marijuana legislation following the drug war).

[46] “If We Don’t Fight, Who Will?”: Activists Demand Reparations for Ex-Cons Convicted of Marijuana Charges in Illinois, CBS Chicago (Jul. 11, 2021) https://www.cbsnews.com/chicago/news/illinois-marijuana-convict-reparations/.

[47] Id.

[48] Avens, supra note 37.

[49] Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Case for Reparations, Atlantic (Jun. 2014), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

The Election Integrity Act of 2021: Georgia Prepares to Overcome New Restrictive Bill

*Ryan Ricketts

I. Introduction

Election integrity issues have become a major concern to the public and the legal profession “[d]ue to foreign interference in the election process, the rapid spread of disinformation, and litigation challenging changes to election procedures made by many states in response to the coronavirus pandemic.”[1] The 2020 pandemic provided Americans with an unforgettable lesson on the importance of election officials to our country’s democracy.[2] The Covid-19 pandemic opened a lively debate about expanding special voting arrangements.[3] These arrangements, i.e., early voting, postal voting, proxy voting, etc., allowed voters to exercise their right to vote by alternative means other than casting a ballot in person at their respective polling station on election day.[4] However, these modifications were temporary in response to the coronavirus outbreak.[5] Now fast forward to the present, in the wake of a flood of disinformation about the election process, state legislatures have taken steps to strip election officials of the power to run and certify elections, centralizing power in their own hands over processes “intended to be free of partisan or political interference.”[6] These dominating state legislatures and politicians are using “election integrity” as a way to rationalize their efforts to further suppress and restrict voters.[7]

II. Georgia Senate Bill 202

The Election Integrity Act of 2021, originally known as the Georgia Senate Bill 202 (Senate Bill 202), is a law in Georgia that further restricts the elections process in the state.[8] The 98-page Bill mandates voter identification requirements for absentee ballots, limits the use of ballot drop boxes, expands in-person early voting, and alters the structure of the State Elections Board to bolster the legislature’s power and give the Board more authority to discipline local officials.[9] In addition, the Bill significantly shortened the window in which voters could request mail-in ballots, which Georgia voters used in record numbers in 2020 amid the pandemic.[10] This legislation received widespread criticism from Democrats and voting rights groups.[11] In the June 2020 presidential and congressional primaries and during early voting for the November presidential election, volunteers with groups like Black Voters Matter brought water and pizza to voters waiting in long lines.[12] Senate Bill 202 makes it a crime for outside groups to give food or water to voters waiting in line in order to solicit votes.[13] Section 33 of the Bill states:

No person shall solicit votes in any manner or by any means or method, nor shall any person distribute or display any campaign material, nor shall any person give, offer to give, or participate in the giving of any money or gifts, including, but not limited to, food and drink, to an elector, nor shall any person solicit signatures for any petition, nor shall any person, other than election officials discharging their duties, establish or set up any tables or booths on any day in which ballots are being cast.[14]

With highly competitive midterm elections approaching in Georgia, voting rights activists claim Senate Bill 202 is a “thinly veiled effort to make it harder for non-white voters to cast a ballot.”[15] In a politically divided and racially diverse state such as Georgia, voter turnout is crucial.[16] Even if a small number of voters are disenfranchised, it could make a huge difference in the outcome of elections.[17]

III. Racial Backlash

Some have argued that this Bill is nothing more than a game of partisan politics, with Republicans seeking electoral majorities for their party by hindering the voting power of non-whites. Senate Bill 202 had and will continue to have a significant impact on voters of color—there is speculation that it was not “an accident or unknown to legislators that these communities would ultimately be affected.”[18] These tactics are traditionally the type of restrictions intended to impact voters of color.[19] President Joe Biden won Georgia two years ago, becoming the first Democratic presidential nominee to break through the GOP stronghold since former President Bill Clinton’s victory in 1992.[20] This contributed to what the Brennan Center for Justice calls “racial backlash;”[21] a theory describing how white Americans respond to a perceived erosion of power and status by undermining the political opportunities of minorities.[22] Racially diverse states controlled by Republicans are far more likely to introduce and pass restrictive provisions than very white homogenous states under Republican control.[23] The effects of Senate Bill 202 were displayed in Georgia’s 2022 primary, where “the turnout gap between white and Black voters was wider than any other election in the past decade.”[24] The lack of turnout caused several observers to question whether the law had suppressed voter turnout and deterred Georgians from casting their votes.[25] However, the real test for these restrictions will likely come in future elections.[26]

IV. Potential Problems and the Communities’ Response

Senate Bill 202 allows any Georgia voter to challenge an unlimited number of other voters in their county.[27] This provision led to consequences after the state’s May 24, 2022 primary election and foreshadows potential problems for future elections.[28] Under Senate Bill 202, counties are required to look into the voter challenges, forcing the counties to reallocate resources that would otherwise go towards preparing for the election.[29] According to the New Georgia Project, a voting rights group that is tracking the impact of the new law, “about 64,000 challenges were filed statewide—with about 37,000 of them in [the] Atlanta area alone—and at least 1,800 mostly Black or Democratic voters’ names already have been removed from [Georgia’s] voter rolls.”[30] Zach Manifold, the election supervisor in Gwinnett County, said in an interview that “[sorting through voter challenges] is not [going to] be a fast process. It’s [going to] take [the County] some time. . . [i]t definitely pulls resources from other things that were definitely starting to ramp up for the upcoming elections.”[31] Nevertheless, voting organizations such as the Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda and Fair Fight have sought ways to engage and encourage poll workers and election boards across the state to address capacity and education on a larger scale.[32] These efforts will continue in hopes of calling attention to the many changes prompted by the Georgia Senate Bill 202 and aiding the minority voters most impacted by the law.[33]

V. Conclusion

Fifty-six years ago, on March 25, 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. called for the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 from the steps of the capitol in Montgomery, Alabama.[34] Georgia’s new law has abandoned their native son by codifying mass disenfranchisement and intimidation, while further suppressing the voting process.[35] Senate Bill 202 attacks absentee voting, criminalizes Georgians who give a drink of water to their neighbors, allows the State to takeover county elections, and retaliates against the elected Secretary of State by replacing him with a State Board of Elections Chair chosen by the legislature and not by voters.[36] This bill was passed to tamp down Black political empowerment.[37] The state takeover of Georgia’s local board or elections will undermine Black political participation and power—potentially putting Black communities, and democracy, in peril.[38] Voter suppression kills democracy—therefore the fight must continue against state legislatures and politicians using “election integrity” as a way to rationalize their efforts to further suppress and restrict voters.[39]

*Ryan Ricketts is a second-year day student at the University of Baltimore School of Law, where he is a Staff Editor for Law Review and a member of the Royal Graham Shannonhouse III Honor Society. Additionally, Ryan serves as a Law Scholar for Professor Ziaja’s Property class. During summer 2022, Ryan was a summer associate at Ballard Spahr LLP and looks forward to returning to the firm in summer 2023. He hopes to continue working in private practice after graduation.

[1] Election Integrity and Civic Education, Am. Bar Ass’n (June 1, 2022), https://www.americanbar.org/advocacy/governmental_legislative_work/priorities_policy/election-integrity-and-civic-education-/.

[2] Election Integrity, Brennan Ctr. Just., https://www.brennancenter.org/issues/defend-our-elections/election-integrity (last visited Jan. 3, 2023).

[3] Erik Asplund, et al., Elections and Covid-19: How special voting arrangements were expanded in 2020, IDEA Feb. 25, 2021), https://www.idea.int/news-media/news/elections-and-covid-19-how-special-voting-arrangements-were-expanded-2020.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] “Election Integrity” Act is Jim Crow 2.0 Voter Suppression, We Are Democracy NC, https://democracync.org/research/election-integrity-act-is-jim-crow-era-voter-suppression/ (last visited Jan. 3, 2023).

[8] Carlisa N. Johnson, The ‘All-Out’ Effort to Overcome Georgia’s New Restrictive Voting Bill, Guardian (Oct. 2, 2022), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/oct/02/sb202-georgia-voting-rights-midterm-elections.

[9] Grace Panetta, Georgia’s New Controversial Voting Law Bans Volunteers, Bus. Insider (Mar. 26, 2021), https://www.businessinsider.com/ga-voting-law-bans-volunteers-from-delivering-food-water-to-voters-2021-3.

[10] Sam Levine, ‘Death by a Thousand Cuts’: Georgia’s New Voting Restrictions, Guardian (Oct. 5, 2022), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/oct/05/georgia-voter-suppression-registration-challenges.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Beth Daley, Georgia’s GOP Overhauled the State’s Election Laws in 2021, Conversation (Oct. 22, 2022), https://theconversation.com/georgias-gop-overhauled-the-states-election-laws-in-2021-and-critics-argue-the-target-was-black-voter-turnout-not-election-fraud-192000.

[17] Levine, supra note 7.

[18] Johnson, supra note 5.

[19] Id.

[20] Gregory Krieg, Early Voting Begins in Georgia with Slate of Key Races on the Ballot, CNN Politics (Oct. 17, 2022), https://www.cnn.com/2022/10/17/politics/georgia-early-voting-senate-house-governor/index.html.

[21] Sara Loving, How Voter Suppression Legislation Is Tied to Race, Brennan Ctr. Just. (Oct. 3, 2022), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/how-voter-suppression-legislation-tied-race.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Loving, supra note 18.

[25] Alex Samuels, Why Georgia’s Turnout Numbers Don’t Tell Us Enough, Five Thirty Eight (June 6, 2022), https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-high-turnout-in-georgia-doesnt-mean-voting-restrictions-havent-had-an-effect/.

[26] Id.

[27] Daley, supra note 13.

[28] Id.

[29] Levine, supra note 7.

[30] Daley, supra note 13.

[31] Levine, supra note 7.

[32] Johnson, supra note 5.

[33] Id.

[34] Georgia’s Anti-Voter Law (SB 202), ACLU Georgia, https://acluga.org/georgias-anti-voter-law/ (last visited Jan. 9, 2023).

[35] Id.

[36] Id.

[37] Domingo Morel, As Georgia’s new law shows, The Washington Post (Apr. 1, 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/04/01/georgias-new-law-shows-when-black-people-gain-local-power-states-strip-that-power-away/.

[38] Id.

[39] “Election Integrity” Act is Jim Crow 2.0 Voter Suppression, supra note 4.

Ghost Guns in Charm City: Mayor & City Council of Baltimore v. Polymer80, Inc.

*Paige Boyer

I. Introduction

Ghost guns haunt cities across America.[1] They are as spooky as they sound—ghost guns are untraceable because they lack a serial number and often the purchaser assembles them.[2] In the first four months of 2022, Baltimore Police Department (BPD) recovered 131 ghost guns, double the amount recovered in the same time in 2021.[3] A shocking ninety-one percent of ghost guns BPD recovered came from a Nevada corporation known as Polymer80.[4] Polymer80 is a major ghost gun manufacturer and sells unassembled guns across America.[5]

Polymer80 describes itself as providing its customers with firearms and accessories “to participate in the build process, while expressing their right to bear arms.”[6] The company’s motto is: “Engage Your Freedom.”[7] Polymer80 claims to sell legally across America because its guns are never more than eighty percent complete and therefore do not meet the manufacturing standards of the Gun Control Act of 1968 to qualify as a firearm.[8] However, Polymer80 sells build kits with all the necessary parts and instructions for assembly of a one-hundred percent complete gun.[9] Consider Polymer80 the “IKEA of firearms.”

II. Challenges to Polymer80

A few jurisdictions have enacted legislation or filed suit against Polymer80.[10] Nevada enacted legislation outlawing the sale and possession of ghost guns.[11] Polymer80 quickly filed suit against Nevada, winning and striking down the part of the statute that essentially prohibited Polymer80 sales.[12] With such a defeat, it may seem daunting to go up against Polymer80, but the District of Columbia (D.C.), the City of Los Angeles (L.A.), and the City of Baltimore are up for the challenge.[13]

Baltimore is the most recent jurisdiction to file suit, after L.A. and D.C. respectively.[14] L.A. initially filed suit on February 17, 2021.[15] Recently, on February 22, 2022, L.A. filed a motion to compel—perhaps signaling that Polymer80 is not eager to cooperate.[16] On August 10, 2022, after over two years of litigation, D.C. was granted summary judgment against Polymer80, and the court awarded a permanent injunction and damages.[17]

III. District of Columbia v. Polymer80

On June 24, 2020, D.C. filed suit against Polymer80 for violations under D.C.’s Consumer Protection Procedures Act (CPPA) and D.C.’s Firearm Control Regulations Act of 1975 (FCRA).[18] D.C. alleged that Polymer80 incorrectly asserted that its products are legal in D.C. when its products violate the FCRA, thereby violating the CPPA and misleading consumers on a material fact.[19] The FCRA prohibits the sale of any unregistrable firearm and the possession of any unregistered firearms, which Polymer80’s unmarked ghost guns violate.[20]

In opposition to D.C.’s motion for summary judgment D.C. on March 21, 2022, Polymer80 claimed that not only were its goods not firearms under the FCRA but that new legislation on ghost guns puts the burden on the consumer to serialize and register Polymer80’s products.[21] The court found Polymer80’s arguments unconvincing and granted summary judgement in part for misrepresentation under the CPPA and selling illegal firearms to D.C. consumers under the FRCA.[22] The court denied the motion for summary judgement in part as it pertains to the element of material fact under the CPPA.[23] The court granted a permanent injunction and payment of four million dollars in relief.[24] After the case in Nevada, this win in D.C. offers Baltimore motivation and persuasive authority in its legal pursuit against Polymer80.[25]

IV. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore v. Polymer80

On June 1, 2022, Maryland banned the sale of any unfinished or unserialized firearm frames and receivers.[26] Immediately following the enactment of this legislation, Baltimore filed suit against Polymer80 for public nuisance, negligence, and violations of the Maryland Consumer Protection Act.[27]

In its complaint, Baltimore alleged that Polymer80 “intentionally undermines federal and state firearms laws,” such as the Federal Gun Control Act and recent Maryland firearm laws, by selling its firearms and knowingly selling to those prohibited from owning firearms, including felons and children.[28] Baltimore claimed that Polymer80’s negligence and their misleading advertisements created a public health crisis.[29] The City alleged that not only were its violations of the law predictable, but the violations foreseeably escalated gun violence in Baltimore.[30] Further, Polymer80 is alleged to have supplied known criminals with its building kits without conducting minimal requisite background checks—furthering violence and crime in the city.[31]

Baltimore has requested a permanent injunction, damages, and an abatement fund to remedy the harms Polymer80 has inflicted on the city.[32] After Polymer80 was ordered to pay damages to D.C. in their previous case, Baltimore’s relief requests seem more likely to be granted.

V. Conclusion

The addition of negligence claims in Baltimore’s suit is a shift from D.C.’s strategy of consumer protection and gun law violations, but it may increase the damages awarded to Baltimore.[33] While D.C.’s win on summary judgment may offer persuasive legal authority, L.A.’s hurdles in discovery with Polymer80 indicates a win for Baltimore will not come easy.[34] These legal battles and attempts to curb the epidemic of ghost guns may push Congress to ban them for good—an outcome that would benefit all cities involved.[35] Gun control, crime, and violence have continued to plague Baltimore and its residents, but Charm City is fighting back.[36]

*Paige Boyer is a second-year evening student and Staff Editor for the University of Baltimore Law Review. Paige has been a member of the University of Baltimore community since 2019. She graduated with her Master of Public Administration in December 2021 and is currently working for the University’s Office of Human Resources. After graduating with her J.D., Paige is interested in pursuing a legal career in child advocacy and public interest law.

[1] Anjeanette Damon, Why Outlawing Ghost Guns Didn’t Stop America’s Largest Maker of Ghost Gun Parts, ProPublica, (Aug. 24, 2022) https://www.propublica.org/article/nevada-ghost-guns-polymer80-firearms-laws.

[2] Ghost Guns, Meriam-Webster Online Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ghost%20gun (last visited Jan. 3, 2023).

[3] Mayor & City Council of Baltimore v. Polymer80, Inc., No. 24-C-22-002482, 2022 WL 1810013 (Md. Cir. Ct. filed June 1, 2022) (trial pleading).

[4] Id.

[5] About Polymer80, Polymer80, https://www.polymer80.com/about-us (last visited Jan. 3, 2023).

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] District of Columbia v. Polymer80, Inc., No. 2020 CA 002878 B., 2020 WL 13526473 (D.C. Super. Ct. 2020) (trial pleading).

[9] Id.

[10] Damon, supra note 1.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Damon, supra note 1.

[15] People of the State of California v. Polymer80, Inc., No. 21STCV0657 (Super. Ct. Cal. L.A. filed Feb. 17, 2021) (complaint).

[16] People of the State of California v. Polymer80, Inc., No. 21STCV0657 (Super. Ct. Cal. L.A. filed Feb. 22, 2022) (motion to compel).

[17] See infra Part III.

[18] District of Columbia v. Polymer80, Inc., No. 2020 CA 002878 B., 2020 WL 13526473 (D.C. Super. Ct. 2020) (trial pleading).

[19] Id.

[20] D.C. Code § 7-2504.01(b); D.C. Code § 7-2502.02.

[21] District of Columbia v. Polymer80, Inc., No. 2020 CA 002878 B., 2022 WL 3336386 (D.C. Super. Ct. Aug. 10, 2022) (trial order).

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Id.

[25] Damon, supra note 1.

[26] Md. Code. Ann., Pub. Safety § 5-703(a)(1) (West 2022). A firearm frame is the part of a gun that house the gun structure including “the hammer, striker, bolt, or similar primary energized component prior to…the firing sequence.” 27 C.F.R. § 478.12(a)(1) (2022). A firearm receiver is the part of a gun “that provides housing or a structure for the primary component designed to block or seal the breech prior to…the firing sequence.” 27 C.F.R. § 478.12(a)(2) (2022). Both structures vary depending on the type of firearm in question. See 27 C.F.R. § 478.12 (2022).

[27] Mayor & City Council of Baltimore v. Polymer80, Inc., No. 24-C-22-002482, 2022 WL 1810013 (Md. Cir. Ct. filed June 1, 2022) (trial pleading).

[28] Id. at ¶ 2.

[29] Id. at ¶ 53.

[30] Id. at ¶ 53–8.

[31] Id.

[32] Id.

[33] See supra Part III.

[34] See supra note 15 and accompanying text.

[35] See Damon, supra note 1.

[36] See supra Part IV.