*Devyn King

I. Introduction

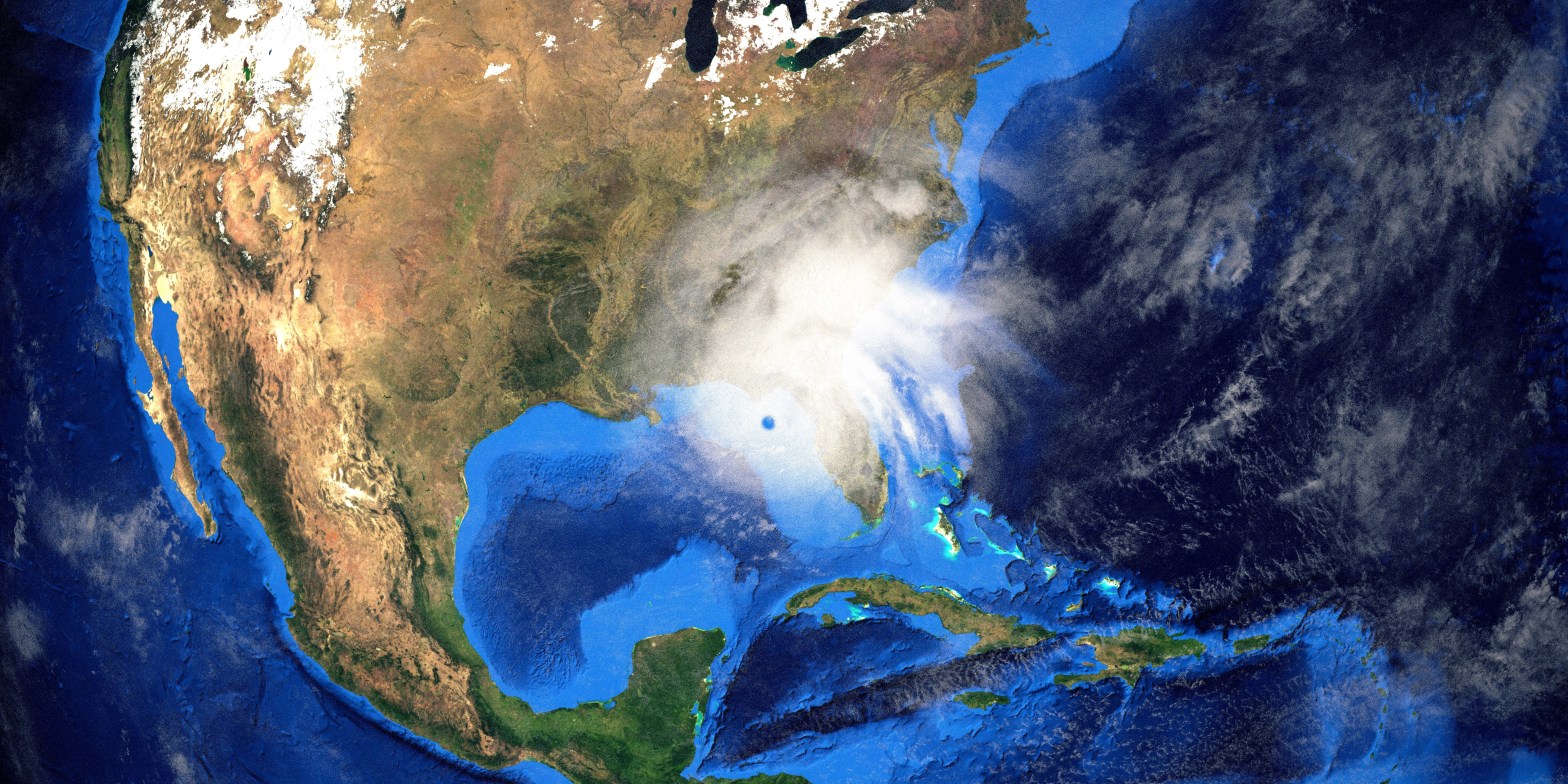

Last year, Airbnb published users’ travel trends for Summer 2022.[1] Perhaps unsurprisingly, domestic travelers sought mostly coastal stays.[2] Florida was the application’s top destination for summer travel.[3] However, in late September 2022, Hurricane Ian made landfall in Florida.[4] The storm was a category four hurricane and caused as much as a foot of rain, flooding some areas of the state.[5] The flooding led to widespread power outages, blocked roadways, and placed some cities under evacuation orders.[6] The havoc Hurricane Ian caused made it impossible for travelers with Florida vacation plans to follow through with their reservations.[7] After canceling their Airbnb reservations due to the hurricane, many travelers were surprised to learn that Airbnb’s Extenuating Circumstances policy did not allow them to cancel without penalty but instead placed them at the mercy of their individual hosts for a refund.[8] Some hosts were understanding enough to issue full refunds, but others were not.[9]

II. Take a Rain Check: Force Majeure Clauses

A force majeure, also referred to as an “act of God,” is “an event or effect that can be neither anticipated nor controlled; especially an unexpected event that prevents someone from doing or completing something that a person had agreed or officially planned to do.”[10] The occurrence of a force majeure event will excuse performance under a contract.[11] This is premised on the idea that the law should not penalize someone for a failure to perform due to an event beyond their control, or one that they could not reasonably foresee unless they expressly agreed to assume liability in such event.[12]

When drafting a contract, parties may negotiate a force majeure clause so that each party knows which events or extenuating circumstances will prevent performance.[13] Courts typically give effect to the specific language the parties define in a contract.[14] This includes the circumstances in which the force majeure clause applies and the procedures to follow in the event one occurs.[15] Since Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005,[16] force majeure clauses have become more critical to account for potential natural disasters.[17] However, treating hurricanes as a force majeure has caused disputes regarding foreseeability. While it may be reasonably foreseeable to experience a hurricane in an area prone to tropical storms, the possibility of catastrophic storms causing extreme flooding is statistically remote.[18]

III. When It Rains, It Pours: Airbnb’s Extenuating Circumstances Policy

Booking a short-term rental through Airbnb includes agreeing to its Extenuating Circumstances Policy, which outlines how the company handles cancellations when force majeure events “make it impracticable or illegal to complete [a] reservation.”[19] Under the policy, travelers can cancel their reservation and receive a refund or travel credit when an unforeseen event impacts their trips.[20] The policy lists scenarios that qualify as an “event”; including changes to government travel requirements, such as visa or passport issues, government-declared emergencies or epidemics, government-imposed travel restrictions that prohibit travel to or from particular locations, military actions, and “natural disasters, acts of God, large-scale outages of essential utilities, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and other severe and abnormal weather events.”[21]

However, the policy expressly excludes “weather or natural conditions that are common enough to be foreseeable in that location—for example, hurricanes occurring during hurricane season in Florida.”[22] The Airbnb website lists precisely which weather events—and in which months they occur—are excluded from the Extenuating Circumstances Policy.[23] From June through November, hurricanes occurring along the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea, and practically the whole East Coast do not qualify as force majeures.[24] In such a case, a host cancellation is the only avenue for a refund.[25]

IV. Today’s Forecast: Cloudy with a Low Chance of Success

Airbnb’s Extenuating Circumstances policy allows cancellation without penalty when it is “impracticable or illegal to complete [a] reservation.”[26] Completing a reservation certainly became impracticable for travelers who faced flooded roadways, toppled infrastructure, and widespread power outages.[27] Additionally, many affected travelers canceled their reservations because their destinations had mandatory evacuation orders in place.[28] The Fifth District Court of Appeal of Florida previously stated, “a governor’s executive order is not a law, but it has the force and effect of law,”[29] but did not directly resolve the issue of whether ignoring a mandatory evacuation order would constitute a violation of a law.[30] Until the courts or the legislature clarify this issue, it is uncertain whether affected Airbnb guests could successfully challenge the Extenuating Circumstances Policy by arguing it would be illegal to complete their reservations under an evacuation order.

Nevertheless, Airbnb’s Extenuating Circumstances Policy expressly excludes hurricanes in September and October for reservations in Florida.[31] By agreeing to its terms, travelers assume the risk of a cancellation due to any non-qualifying event under the policy.[32] Because courts typically give effect to the express language agreed to by the parties, any challenges to the Extenuating Circumstances Policy by affected travelers will likely fail.[33]

V. Conclusion

Through no fault of their own, but merely due to an inauspicious force majeure clause and settled contract law principles, Airbnb guests are left to their hosts’ kindness to provide refunds after canceling in the wake of Hurricane Ian.[34] To avoid potential liability for incomplete reservations due to future unforeseen circumstances, guests should check what, if any, events are expressly excluded from the rental platform’s force majeure policy before booking a short-term rental.

*Devyn King is a staff editor for Law Review and a second-year student at the University of Baltimore School of Law. She is currently the Vice President of the Students Supporting the Women’s Law Center chapter at UB and is a teaching assistant for Introduction to Lawyering Skills/Civil Procedure I. Devyn is also a Distinguished Scholar of the Royal Graham Shannonhouse III Honor Society and a proud graduate of the University of Pittsburgh. In 2022, Devyn worked as a summer associate for Gallagher Evelius and Jones LLP. After receiving her J.D., Devyn hopes to work as a transactional attorney in Baltimore City.

[1] Airbnb 2022 Summer Release Highlights, Airbnb News (May 11, 2022), https://news.airbnb.com/airbnb-2022-summer-release-highlights/.

[2] Id.

[3] See id.

[4] See Michael Tobin, Airbnb Guests Are at the Mercy of Hosts for Hurricane Refunds, Bloomberg (Sept. 29, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-29/airbnb-guests-must-rely-on-hosts-for-hurricane-ian-refunds?leadSource=uverify%20wall.

[5] See id.

[6] See id.

[7] See id.

[8] See Hannah Towey, Airbnb’s Refund Policy Specifically Excludes Hurricanes in Florida Because They Are ‘Common Enough to be Foreseeable,’ Business Insider (Oct 5, 2022) https://www.businessinsider.com/airbnb-refund-policy-booking-host-cancellations-hurricane-ian-florida-aircover-2022-10.

[9] See id.

[10] 30 Richard A. Lord, Williston on Contracts § 77:31 (4th ed. 2022) (citing Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019)).

[11] Id.

[12] See Farnsworth v. Sewerage & Water Bd. of New Orleans, 139 So. 638, 641 (La. 1932).

[13] See Jennifer Sniffen, In the Wake of the Storm: Nonperformance of Contract Obligations Resulting from A Natural Disaster, 31 Nova L. Rev. 551, 553 (2007).

[14] See 30 Lord, supra note 10.

[15] See Force Majeure Issues Relating to Katrina, Jones Walker (Sept. 21, 2005), https://www.joneswalker.com/images/content/1/1/v2/1176/249.pdf.

[16] Extremely Powerful Hurricane Katrina Leaves a Historic Mark on the Northern Gulf Coast, Nat’l Weather Serv. (Sept. 2022), https://www.weather.gov/mob/katrina.

[17] See Sniffen, supra note 13 at 553.

[18] Force Majeure Issues Relating to Katrina, supra note 15.

[19] Extenuating Circumstances Policy, Airbnb, https://www.airbnb.com/help/article/1320/extenuating-circumstances-policy (last visited Oct. 23, 2022).

[20] See id.

[21] Id.

[22] Id.

[23] See Weather Events, Natural Conditions, and Diseases That Are Excluded From Our Extenuating Circumstances Policy, Airbnb, https://www.airbnb.com/help/article/2930/weather-events-natural-conditions-and-diseases-that-are-excluded-from-our-extenuating-circumstances-policy (last visited Oct. 23, 2022) [hereinafter Weather Events].

[24] See id.

[25] See Tobin, supra note 4.

[26] Extenuating Circumstances Policy, supra note 19.

[27] See generally Patricia Mazzei et al., Hurricane Ian’s Staggering Scale of Wreckage Becomes Clearer in Florida, N. Y. Times (Sept. 29, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/29/us/hurricane-ian-florida-damage.html (explaining the damage resulting from Hurricane Ian throughout Florida).

[28] See Tobin, supra note 4.

[29] Gillyard v. Delta Health Grp., Inc., 757 So. 2d 601, 603 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2000).

[30] See id.

[31] See Weather Events, supra note 23.

[32] See Extenuating Circumstances Policy, supra note 19.

[33] See 30 Lord, supra note 10.

[34] See Tobin, supra note 4.